John Porcellino

For close to a quarter century, John Porcellino emerged with King Cat Comics as a central figure on the self-published field of comics, sticking to an approach that is both personal and fragile. With his unmistakable line and his stories dealing with the simple things in life, he has built along the years a unique and fascinating body of art.

Xavier Guilbert : You’re currently working on King-Cat Comics #74 and next year will mark 25 years of King-Cat Comics — how did it all begin ?

John Porcellino : Hm… well…

Xavier Guilbert : Did you have any idea that it would last this long ?

John Porcellino : I will say — like, I would always make little books and stuff as a kid, and then … in high school I would make little Xeroxed books, and give them to my friends and stuff. When I went off to college, it was I think 1987 when I discovered that there were all these people doing ‘zines, you know ? And as soon as I discovered that network of people all over the world, doing those self-published little books, that’s where I felt at home. Instantly, I was like — this is it, I love this.

Xavier Guilbert : Those weren’t just comic ‘zines, but ‘zines in general ?

John Porcellino : Yeah. I mean, comics — in the early ‘zines days, like in the ’80s, which I kinda miss, is that it was very broad. I mean they still are, but like — I was doing King-Cat, but I would get in the mail political ‘zines, or just poetry, or any kind of weird thing. And we would trade back and forth, you know ? So over time, comics became kind of its own … the only stuff I get in the mail anymore is comics. It became its — the thing got separated, when at one time it was just a big soup of people. It was more — it wasn’t like : “Oh, you do comics ? I do comics” and you would trade or connect. But it was more : “Oh, you publish a ‘zine ? I do too. Mine happens to be comics, but…” But the ‘zines I was doing, I was more an editor. I would contribute things to it but I would gather people’s work and put it together. And it was in — it must have been in 1988, when I discovered Julie Doucet. She did Dirty Plotte. I had seen things like this, it wasn’t something totally new, but the thing that struck me was — it was all her work. Which other people had done, but for some reason it didn’t strike me the way it did when I saw her thing. It just seemed so personal. And that was my inspiration to start King-Cat. So I started this new ‘zine — and I did other things on the side, other titles and things. But once I started King-Cat, that was just where all my energy went. I loved it. And so, pretty early on, my whole thing with King-Cat was : this could be anything. Whatever is going on in my life at the time, I can put it in it. So it can constantly evolve and change. And I realized it could be a long-term thing, you know ? Because I wasn’t going to be tied to a certain character — I mean, except for the John P. character. But like, a certain style, type of story, or anything. It could just keep changing as I changed.

Xavier Guilbert : Where you doing autobiographical stuff prior to discovering Julie Doucet ?

John Porcellino : Yes. As a kid, I did stories about swords and sorcery, and like, James Bond, spy stories and stuff. But when I got to high school, my comics became more… I started to do some autobiography. Or more — even if it wasn’t necessarily stories about my life, but more personal kind of things.

Xavier Guilbert : Was that an aspect that was encouraged in the teaching you received in arts school ?

John Porcellino : When I look back, I don’t know why, but I was just always interested in that. I say — I’m interested in this thing called “real life”. Which is like, really, experiencing being alive. It’s kind of difficult to describe. But even when I was in — I was a painter, you know ? All my works, whether it was music (because I played music) or wrote, or did comics or things like that, they all had their inspiration in some real experience. Either mine, or something I would read in the paper, or a friend would say or something like that. That’s just always been my interest, from pretty early on. In fact, the early days of King-Cat, there were not a lot of people doing autobiography. In fact, the only person I can think of was Harvey Pekar. You know, American Splendor. And people would pick up King-Cat and be like : “Do you know Harvey Pekar ? You should read this thing”. And so for years and years, I purposely never — I would see it on the racks and I wouldn’t even pick it up, because I didn’t want — I was like “Oh, that’s the guy who does things like me, they say”. And I didn’t want what I did to be tainted. I wanted to be able to say : “This is just what I do, I didn’t take it from someone”. And then Chester Brown and Yummy Fur, in the early 90s, he switched over to autobiography, and I was like — “Oh, now it’s over”. Because everybody is going to think that I’m copying Chester. But I was quietly doing it on a very small level for those years before. It’s been, I don’t know why, but autobiography is now its own genre in comics. But for me, it was always the way I thought. I mean, in the early King-Cats, there would be some fictional pieces. But even those were based on some kind of real experience. I would just change the names. It would be me, but I’d call him “Billy” or something instead. Every once in a while I do something fictional or weird or silly or something that just comes to me, but most of it is just the way it is. I just think — to me, my art is about experiencing life, and thinking about it and then communicating that to other people. So… That was the other thing I realized too, with doing King-Cat this way : as long as I am alive, I’ll have new material. And maybe it will be boring or it will change, but things will always be happening and there’ll always be something to write about. When I started thinking in that way, that’s when I realized this could go on for a long time. It could go on for as long as I wanted to do it.

Xavier Guilbert : You said that at the beginning, you distributed King-Cat around you. But doing autobiography and distributing to the people closest to you, friends and relatives — how did it go at the beginning, and has it changed since ?

John Porcellino : Well, most people like it. They get a kick — even old friends that I don’t really have contact with. If they are in the new issue, I’d put it in the mail and be “hey, you’re in the new King-Cat !”. I mean… I mostly write about my friends, and I like my friends, so… we get along. So usually it’s not too much — I’m not writing, I’m not giving their secrets away or anything. It is very friendly, and affectionate, mostly. So usually, there’s not too many problems. Sometimes, I want to write about something that I think… it occurred to me at some point that even though I’m very open about everything, other people may not wish to have some story told to strangers. And so, if I feel there’s a question, I’ll talk to people about it sometimes and go : “I wanna do this story, do you have a problem with it ?” Which is helpful, actually, because sometimes then I’ll talk to them about it, and then they’ll tell me things about… I’ll be like : “Hey, do you remember that one night we all went to the railroad bridge ? I was gonna do a story about that, is that okay ?” And it’ll start a conversation, and we’ll talk about it, and they’ll remember things about it that I didn’t remember. So it’s actually kind of helpful to do that. But mostly, I don’t do comics as revenge, or to hurt people. So generally, I think that people are okay with it. I think a few times I have probably hurt some feelings, but nothing lasting — nothing with lasting damage.

Xavier Guilbert : How many copies did you make of the first issue ?

John Porcellino : 18. The first couple were 18, and then I tried to…

Xavier Guilbert : Why that number ? That sounds a bit strange, not to go to … 20, for instance.

John Porcellino : (laughs) It was like — I think, because : I kept one ; I gave one to my dad ; I had like six friends or something ; there was maybe… there was Factsheet 5, do you know about that ? Factsheet 5 was a magazine in the 80s and the 90s, that — this was before the Internet, right ? So it was kind of “information collection” about small press, about self-published books. You would do a ‘zine and send it to Factsheet 5, and then, a couple of months later, you’d get in the mail this big, thick newsprint magazine that just listed hundreds and hundreds of ‘zines, with their address and “send a dollar” or “send a stamp” or “trade”, and it would have a little description of what was in that issue. And that’s how people connected. So I would get Factsheet 5 in the mail, and I would have my little review of King-Cat #3, but it would also have these other hundreds, and I would sit and read through all those descriptions and make little marks. “I want to send away for this”, or “these people say they’ll trade and it sounds interesting so I’ll send King-Cat to them”.

So I’d send one to Factsheet 5, and then I’d keep five off to the side in case somebody orders it from Factsheet 5. And so it just — that’s all I needed, you know ? There are very very few people who probably have every issue, because the first year or six months… I think Julie Doucet, if she kept them — I don’t know if she did — she would have them because I was so inspired… We started up a conversation and became good friends then, after — through Factsheet 5. So I would always send up to her or my best friend Donal. I sent him every issue. But those early ones, there weren’t many of them. Which is fine.

Xavier Guilbert : When did it start to pick up ?

John Porcellino : Oh, it just kind of gradually… each time I would increase the print run, or… I would just make 20 copies, and when they were gone, I would go back to the copy shop and make some more. And at a certain point, it became a pain in the butt to do that. I’d just print 500 of them and I wouldn’t have to worry about it for the next year or two. So that’s kind of how it’s been. I do an issue, and for some reason I run out of them quicker than usual, then I’ll increase the print run next time. Now, I do 2,000, give or take. If that sells out fast, I may do a few — you know, an extra hundred or something, but that’s about it.

Xavier Guilbert : Do you still go to the copy place ?

John Porcellino : No, they do it for me. Now, with technology, I just take all the files and press a button, and then it goes to a satellite and the satellite beams it down. They get printed in Denver, still. Because I have a printshop that I’ve used for twenty years. They’re very good to me, and they understand what I’m looking for. But now, with technology, it’s funny. It’s interesting, because the printshop I use, when I started out with them in 1992, 21 years ago, it was a used office furniture store. So it was old, beat-up file cabinets and sofas and chairs, and then in the back, there were photocopiers. And they had a little photocopy desk. They were just the closest place to my house, so I went and I said : “hey, can you just print this ?”

And now, they keep growing. Now, they are in a warehouse by the Denver Airport, and it’s — they have millions of dollars of these giant machines, and binding, and all this digital technology. So it’s funny to still…

Xavier Guilbert : Do they print other ‘zines than yours ? Or is it just you, because you’re like the most-faithful customer they have ?

John Porcellino : (laughs) Yeah, they do kind of roll their eyes at me a little bit, because I’m very particular about it. I think that when I walk in — when I lived in Denver, I would walk in with my pages — I think, at the same time they would be : “oh, John’s here”, and like “pfff…”. Because they are probably used to printing annual reports, business forms and stuff like that. And then I come in and I’m like : “I want this to be like this, and this like that”. So, hopefully, I know for some of the people who worked there I think it was kind of fun to do something different. Some of the people I’ve worked with have been there for a very long time. I still use them because I’m loyal to them.

Xavier Guilbert : How was your art received at the beginning ? (John laughs) And why did you choose that specific style, especially in the light of your studies in art school ?

John Porcellino : Hm… Well, in the ‘zine world, it was fine. People were used to seeing different things — they were used to seeing kind of an amateur… I hate to use that word, but, you know what I mean ? Untrained or rough. And I came out of punk rock too, so… you know what it’s like. It doesn’t matter what it looks like, it matters what it means. Those were my inspirations.

But in the comics world, for a long long time, there was just not a connection between what I did and the comics world. I read comics, I would get the new Dan Clowes comic or whatever was at the shop, but it was just like this thing that was way up here, and me and my friends were down here doing this thing, that was comics, but it was very separate. And when my comics would reach that world, the reaction usually was… “what is this shit ? First of all, he can’t draw. Second of all, the stories aren’t about anything ?” It was not what they were used to seeing at all.

In Art school, making paintings and stuff, to me, it was all part of the same thing : music, ‘zines, painting, writing… but in a lot of ways, it was kind of secret. When I went to Art school, if you said : “I want to be a cartoonist”, I don’t even think they would have laughed. They would have been — disgusted. So I had friends in college who were painters and who would do comics and things, but it just wasn’t… it was only for these very few people who were below the radar. The art people didn’t even know.

But I would, towards the end of my college time, if there would be a show in the art building… they’d have a student show or a senior show or things like that, they’d have these art openings. I would go, I had a little old doctor’s bag, like a leather suitcase ? And I would fill it with ‘zines, I would go there, and I would create like a guerrilla — I’d find a table and I’d drag it in the hallway by the entrance and I would set up my things, and be like : “here is some art for 35 cents !” And I’d have the table, and people would be interested. They kind of laughed or whatever, but I met some people. That was my whole things with ‘zines : I was a painter, and I was an artist, but there were so many thing about the art world I just couldn’t tolerate. I wanted art to be cheap. I wanted it to be accessible to everybody. I wanted it to be multiples, I didn’t like the idea of just having this one thing that somebody would put in a closet somewhere. I wanted it to be out in the world and going around. And so, to me, it was always art. It was just another way of making art. Those are the reasons too I realized this was a long-term thing, because it solved all my problems. At one point I realized, doing these comics is exactly how I want to express myself. In that way. In this form. This is how I want to do it.

All the problems I had with the fine art world or gallery art… coming from a real do-it-yourself background and a punk-rock background, I realized this is not going to work. I have too many, too many strong beliefs about how I want to do things, and comics just solved all that. Especially self-publishing comics. I do it all myself.

Xavier Guilbert : You did really establish a format that was both very unique and personal. A typical King-Cat issue starts with the cover, then the KC Snornose introduction, the letters, the top-40s, and then there’s a mix of drawings and sometimes a typed page or two. It’s a mish-mash of things, in a positive way, which seems pretty coherent with what you said about the origin of ‘zines. With technology, it is now easy to put up a blog and have a result that is — professional-looking, as opposed to your “amateur”. But you’ve stuck to what you were doing, in a way that makes it now unique and immediately identifiable — in the sense that : this is John Porcellino, and there’s no one else like him.

John Porcellino : Well, I hope… When I talk to young cartoonists, that’s what I always say : you have to find a way to be yourself. That’s what it’s all about. Otherwise… everybody goes through early times when you’re looking at things and taking in influences and processing those influences and stuff. But ultimately, you have to find that voice inside you. If you find that voice, what you do is going to be unique. It sounds like hippy stuff (laugh), but everybody is unique, and if you find that source inside you that needs to be expressed, then you’ll do your own thing. You’ll take in, you’ll see other people’s — I certainly have influences that I’ve taken in, and… but from the early days, I was really conscious of like, I just want it to be different. I don’t want it to look like anybody else’s stuff.

All those elements of the King-Cat, it does come from those early days of ‘zines. And also, like I said : this can be anything I want. It doesn’t have to be… like something else. It’s interesting, because I always drew comics, but I did not — many American cartoonists, especially of a certain generation, grew up reading super-hero comics and going up to the comic book store and stuff like that. I had none of that. (pause) I mean, I had a few comic books, but five or six comic books in my whole childhood, that I would just read over and over again. And I would read in the newspaper, the Sunday, the newspaper Funnies. But I think, luckily, I’m grateful. The very first moment I tried to do comics, I felt they could be anything. I didn’t feel I had to do them in a certain way, that it had to be like this, and… to me, it was totally free from the very first moment.

It could be anything. It could be about nothing, it could be this, it could be that. You could put just writing in it, you could just do drawings. You could cut something out from the newspaper and just glue it in and that’s okay too. I’m glad that I didn’t have those restrictions on me.

Xavier Guilbert : Didn’t you get some of those restrictions through the feedback of people on the issues you were putting out ?

John Porcellino : That’s the other thing too, when I talk to young students, I say : I think, with the Internet and things, it’s probably impossible now. Or you could do it, but you’d have to be very disciplined. Like I said, those first issues of King-Cat — 10 copies would go out in the world. Maybe people would write back and say : “Hey, I got the new King-Cat, that was funny”, or whatever. But mostly, I was just sitting there drawing obsessively.

Xavier Guilbert : Especially since you put out a lot of issues at the very beginning.

John Porcellino : Yeah, very fast. I put out 24 issues the first year or something.

Xavier Guilbert : And then it slowed down and now it’s down to once a year. But the first ones were, what, a dozen pages ?

John Porcellino : Yeah, twelve pages, and just like I said, sometimes it would be just stuff I cut out from the newspaper and I’d glue it down and here is the next King-Cat. So it was very very quick, and I didn’t think about it all, I just — I had an idea, I’d put it on paper. I didn’t write it beforehand, I just started and drew it, and when it was done, it was done. I didn’t go back and fix it and clean it up, I just put it in the “done” pile, and when I had the twelve pages, I’d go to the copy shop and that would be the next King-Cat.

Xavier Guilbert : What happened ? When did it change from this “fire-and-forget” approach, to something where there’s a lot of … creative pain process (John laughs) and the fact that it’s not something that’s as easy to do now ?

John Porcellino : It’s just slowing down, and getting older. I think, partially. But also, the first issues, I was still in school, so I had no responsibilities. I may have had a part-time job here and there, but I just was drinking beer, playing my guitar, and writing comics. So it was like — every night, I would sit down and make comics. And then, you grow up and you have to get a job. I actually made it, all the way to — it was King-Cat #44, and that was the first issue that I sat down and realized people were gonna read it.

I had just gone on a trip out west, to the West Coast, to San Francisco and then we went up to Seattle, which is where all the cartoonists lived at that time. And I met all these cartoonists. They were still underground cartoonists : Dave Lasky, Megan Kelso, and I met Julie [Doucet] there, when she was up there in Seattle. A whole bunch of cartoonists. And I realized they take it kind of seriously. You know ? First of all, they had a community. They would sit and they would draw together, they’d look at each other’s work and get comments and stuff like that. And I came back to Denver, where I lived, and I started working on King-Cat #44, and I was like : “Oh shit ! People are gonna look at this !” And I knew from being in Seattle, that they would sit and talk about stuff, they’d be like : “Oh, I like what they did here, but over here, you know, I think it wasn’t that good.” And I was paralyzed.

Xavier Guilbert : But you had correspondences with people, you got things in the mail, but it wasn’t… ?

John Porcellino : No, it wasn’t that way. It was like — I’d send my comic to somebody, and they’d send me theirs, and we would be like : “this is great !” It wasn’t “let’s sit down and figure out how to make our comics better.” It was just very natural. I’m not saying that in Seattle that’s how they were necessarily, but that’s how I perceived it. And when I came back, I was — I’m going to send this to all these people, and they are going to sit down and talk about it. This’d better be good !

That was a turning point for me. I need to make this good, you know ? And ever since, I’ve struggled with that. Part of me misses the old days of — “I don’t give a shit”.

Xavier Guilbert : Looking back at your work, do you see this divide yourself ? Did it actually change your work, or just the way you looked at it ?

John Porcellino : I think I slowed down. Instead of just — with the pen, and scratching it out, I was more… (miming drawing with application) … “okay, that looks good”. Or “I’d better redraw that”. So that really did happen. But at the same time, I think it is just natural. You do something for a long time, and hopefully, it’ll just end up being better anyway. Because you’re doing it over and over and over again. And I mean, I did look in the early issues, I would do my stuff, but I wouldn’t think about it. Nobody taught me how to make comics. So I would do a comic, I’d look at it, and I’d think : “this didn’t come out the way I thought it would. What did I do wrong ?” I was trying to teach myself. But I didn’t worry too much about it, I always felt there would be another comic after this, and I’d try to do better then. I’d try to take the mistakes I had done on this one, and improve on them in the next one. There was no anxiety about it.

After that time of meeting the cartoonists, I did start to have more anxiety about it. Until, a few years later, the anxiety was so bad that I was crippled. It was devastating anxiety. And so now, I try to walk the line between those things. I want it to be good, I want to do a good job… but I also try to keep some of the spontaneity — or bring it back, because I… I’m trying to walk between these two things : pure spontaneity, “I don’t give a shit”, and then on the other hand, “it’s gotta be perfect”. Because it loses something if you kill it that way. You kill it, right, with perfection. And I don’t want to do that.

Now, I’m kind of back to the point where I’ll do a comic and put it in King-Cat, and I’ll look back and be : “hm, I tried something, but maybe it didn’t work that well”. Now I’m learning again.

Xavier Guilbert : It’s interesting what you say about wanting to correct your mistakes. Because there’s one thing that really struck me in King-Cat : there’s the diaristic approach, that kind of documents the things in your life. And you want to be really precise about it, as authentic as possible. With the stories collected in Perfect Example, you say you talked to your friends to try and get it as it was and not just as you remembered it. And there’s a lot of corrections, and in the collections you’ve got the notes, then there’s the additional comics, then the notes on this too, and then notes on the notes… (John laughs) Do you keep a journal for yourself ?

John Porcellino : Yeah, there was a period when I lived in Elgin, Illinois, after my first divorce. I lived for three and four years in relative isolation. I had a job, so I’d see people, I’d go to work, and then I’d come home with me and my cat. And during those years, I kept a journal. That’s the only time I had the discipline to do it consistently. I have one on my desk now, that I’ve written in maybe once a year… I don’t know why.

Xavier Guilbert : And about this need to get things as they were — again, that’s your stuff, and one could think that putting it the way you remembered it was also John Porcellino.

John Porcellino : Actually, when I did Perfect Example and talked to all those people — in some way, I brought that into the story and I started to use that technique. Like I said : “I want to do a story about this, can you tell me what you remember ?” But at the same time, it was kind of liberating, because I realized just what you said : all those different people were in the same place, and they all have different recollections of it. Sometimes, contradictory recollections. And so, in some way, it was liberating because I realized that… I’m not really telling the truth, right ? I’m telling my truth. This is my version of what happened. And even though I will do those notes and be like : “argh, I screwed up, it wasn’t that way”, to me, it’s more just a way of documenting the fact that our perceptions aren’t always accurate. To me, that’s kind of what it is.

But it was freeing to me to realize that… it’s not like journalism. I’m not researching and getting all the facts out and figuring it out and putting this puzzle together — I’m just telling a story. It’s based in life, and I’ll take in other people’s input and think about it, but ultimately, I’ll let the story be what it wants to be. Even if it’s not 100 % accurate. I don’t think that I make stuff up. I won’t invent a character and put him in the story. But I’ll leave things out, or move things around. Sometimes. In Perfect Example, where it’s a long story arc, I certainly did that. I moved one night before another night because it just made the story — it would made the story less confusing or something.

So it freed me up a little bit to realize that everybody has a different truth. Ultimately, there is some truth, but our perception of it is different and is changing all the time… I’m also kind of obsessive, and if I make a mistake, somehow it makes me feel better to own up to it. “I goofed up”. I won’t go back necessarily and change it, but I’ll tell people : “this thing, I was wrong.”

Xavier Guilbert : There’s an interesting aspect in the collections. Map of my heart collect the issues from which Perfect Example was taken. There’s a couple of issues where there’s only a few pages, and then it moves on to the next. When one thinks of a collection, it’s usually a book that is thought to make a whole and be autonomous. Whereas yours definitely refer to something of a grander narrative — that which unfolds within King-Cat, and also references your whole life eventually. The fact that this is only a fragment of something much larger is very much present. To get back to Map of my heart, the issues with the Perfect Example story tell of this long story that is starting, and you thank your friends, and —

John Porcellino : (laughs) and it’s not there !

Xavier Guilbert : It’s all part of this trying to be as authentic as possible, I feel, like not trying to rearrange things.

John Porcellino : Well, it’s interesting to think about it that way. Really — I probably felt that there’s already a book of that stuff, I’m not going to put that book inside this other book.

Xavier Guilbert : But you could have left out the introduction pages that specifically reference what has been left out. Especially since it’s not a collection of everything that was in King-Cat, right ? It’s a selection.

John Porcellino : Yeah, that is important. That’s something that I consciously do with my work, where… a lot of my stories, they are just those little pieces of — one or two pages. But when you take them as a whole, as they stack up, it develops this larger thing. So that was something that I was conscious of from early on. I would do stories where I would refer to something, but I wouldn’t explain it. It would just be some oblique reference to something. Because I knew that at some point there would be a comic that would maybe explain that reference. Maybe it’ll be five years from now. At some point, I realized that I had readers who were willing to invest that effort into it, which was — very gratifying. I had readers who were willing to pick up the new King-Cat and go back ten issues, and be like : “Oooohh, okay.” And so it became some kind of puzzle to me, to put these puzzle clues in the stories that hopefully, at some point, the reader would see where that was. It’s a whole life, you know ?

Xavier Guilbert : What led you to put out this long story, which is, I think, the only one in your whole body of work ? And thinking of how you approached the production of King-Cat at the beginning, how did you get through it ? Did you change your process ?

John Porcellino : Yeah. It was a combination of things. I use that as an example when I talk to students too, because the stuff that happened in Perfect Example happened in the summer of 1986. And the first time I tried to write that story was the fall of 1986. That fall, I sat down and thought : “that was a pretty intense summer. I wanna do something with that.” Whether paintings — I worked on a series of prints and stuff that would be about that summer. I would work on it, in notebooks and things. It just wouldn’t go anywhere, and I would forget about it, and maybe the next year I would pick it up and be like : “what about that story ?” It took me — I started drawing the comic Perfect Example in 1996, so it was ten years after it actually happened. And I think it just took me that long not only to figure out how I wanted to tell the story, but I think, just to have the confidence or the skills to go : “okay, I think I can do this longer story”. A few issues before that, I did a story that was 18 pages. And I was like : “Oh my God, eighteen pages ? that’s crazy !” That inspired me too to … I have this long story, that’s more complicated, with more ins and outs. And I just want to try it. I felt it was time to do it.

The process was very different because I realized I wasn’t going to be able to just spontaneously write eighty pages of comics. I had to think about it, and I knew that there were characters that would appear, and then come back later, and I knew there was a narrative arc to the story. It was a very different process. And in fact, that may be when my writing style changed a little there — I spent a very long time writing it. I had notebooks, and I would make little mock-up copies, and I approached it like sections : “okay, it starts here, then this happens here. But if that happens here, I have to put something in between these two, to explain how I got there.” Putting the book together was like taking these sections and trying to put them in a cohesive order that would tell the story and flow together and provide the information necessary when necessary. It was a very different thing.

Xavier Guilbert : Has it impacted the way you approach the page as a whole ? I have the impression that the pages seemed to me more structured at the end of Map of my Heart. Both in the terms of the layout, but also in the use of blank panels or even blank pages, which is very efficient. Fully using comics as a storytelling device, and not for representation. It’s not about the art, it’s about the way you tell a story.

John Porcellino : It’s true, and there’s a couple of things — I never thought about this, but talking with you, I realize that doing that long story… comics are all about rhythm, you know ? And pacing, and pauses, and emphases and things like that. Certainly before Perfect Example, I was becoming more aware of that and working with those kind of things. Part of what I had to do with Perfect Example was like : okay, I have 72 pages or 76 pages or whatever it is, I have to make this flow cohesively. It wasn’t just like “I need to make this panel flow with the previous one”, but “I need to make this whole thing go”. I had to really start to look and understand how to make that happen. During that process, I became much more aware… for instance, the page breaks, the end of page : now I have a little bit of a gap, where the readers are physically turning the page. And there can be something startling here. Or this is going to have more emphasis because this is the first thing they see when they turn the page. Those kind of things, I became more aware of and interested in experimenting with.

Also, at that time… I had always been interested in poetry and things like that, and I became very much aware of the connections between poetry and comics at that time. I was consciously exploring the ways I could make comics more poetic. I do think that after Perfect Example — well, I mean there’s a couple of things : the major thing, I think, is that during the process of making Perfect Example, I became very very sick. I almost died. In between the two issues, the cartoonist’s worst nightmare. I had the first part of Perfect Example done and published, and then I got sick, and I survived, and so I got to finish the story. That’s my worst nightmare, “it’ll be unfinished !” That experience of getting sick, that, to me, is the hinge in my life. Everything before was one way, and then that happened, and everything was different. I still do King-Cat, there’s consistency. But it changed everything.

Xavier Guilbert : Did you get interested in Zen Buddhism before, or after that moment ?

John Porcellino : It was before, luckily (laughs). Right before, maybe the year before I got ill. Which helped me very much psychologically, to get through that experience.

Xavier Guilbert : Looking at Zen Buddhism, it is very striking how it seemed a perfect match for you, considering the dominating themes in your work, from very early on. The simple pleasures and stuff. How did it happen, how did you get to learn about it ?

John Porcellino : Even before I got very sick I started having some health problems and stuff. I was in my mid-twenties, I was fairly young, but I had lived — I mean, I wasn’t a junkie or anything. I’d drink until I fell down. I was like — a rock’n roll dude. It sounds so stupid to say it that way, but it was just like staying up till 4am, drinking beer all night, then going to Burger King and getting a big sack of burgers and whatever. Then I got sick, I started having those health problems, and I was like… “what ?”

I always was interested in spirituality. I grew up catholic, I went to catholic school. My family wasn’t religious. I went to these schools, and so I had this kind of indoctrination and… I was always interested. It felt like a spiritual life to me. When I started getting sick, I started thinking about those things more.

I don’t even know how I first discovered Zen. The thing, when I found Zen and started learning about it, the way I describe it is : I found an old pair of shoes, and I put them on. And like you said… I had these threads going through my life that were kind of mysterious or these compelling things that I was interested in : the small moments and everyday life and things. When I discovered Zen… I realized right away that these were things I already was pursuing through my art.

Xavier Guilbert : Basically, you found a word to put on things that you were already doing.

John Porcellino : Yes, and that’s how I describe it. I found a framework for me to understand these things that were in the ether in my life. “This is really compelling and interesting, I feel drawn to this, but I don’t really know why…” And Zen gave me a framework for thinking about that, and that was very important to me.

Xavier Guilbert : From that point, some of your stories take on what I would call a “koan-like approach”, as if you were embracing it even further more. There are pages that echo a lot the Japanese haiku.

John Porcellino : Oh yeah. Again, I feel silly saying it out loud. Zen just… infused my whole life. Which is what Zen is, Zen is learning to live your life, right ? Every part of my life became informed by this new approach. You said it too, the approach was there, but it was kind of … at some point, I saw how all those threads related to each other. And it was very influential.

Xavier Guilbert : You did some therapy too, at some point.

John Porcellino : Yeah.

Xavier Guilbert : Did it have any kind of impact ? I don’t know if it has to do with therapy, but there are a lot of things you are very open with. And part of therapy is first acknowledging you need to change. Did it affect your work ?

John Porcellino : Therapy was interesting, because I think I went for the first time when I was thirty. I was… an unhappy, messed-up person basically from the time I was fourteen. We did an exercise here [at PFC#4], Menu had this “oppression” exercise with six panels where we started with age nine through fourteen, and you have to write for each age this oppressive experience or something. I tried to do it, and — my childhood was pretty much fine, you know ? It was until I got to fourteen. If you started this exercise at fourteen, I could write pages about it. When I got to be a teenager, everything got all messed up. I resisted going to therapy, because… mostly, I grew up in the Midwest, and it’s a very different… people don’t talk about their problems here. Everything is kept hidden. You don’t talk openly about things. I think part of it was that. But when I finally went… I had a resistance to it. I remember going in for the first time. I had found this therapist who was a Buddhist, so I thought it would be… so I went in, and I was : “is there really a couch ?” It was a cliché, I was almost laughing. Then I sat down and I started talking.

Xavier Guilbert : So you really laid down on it ?

John Porcellino : I think I did, because I was so anxious. I was really uncomfortable. It was — I thought I should have done that fifteen years ago (laughs). I’m coming to this very late. The thing is, I could only afford it in piecemeal. I just had a lot of anxieties in my life, and depression. Therapy helped me unravel some of the reasons. Some of it I was aware of, I could guess in my life experiences why I would have certain problems. It was helpful.

Xavier Guilbert : To get back to Zen, do you take courses, do you have some kind of mentor ? Or is it just a personal thing ?

John Porcellino : I started practicing on my own. After a few years of that, I kind of realized I needed some guidance. If you’re sitting by yourself and you’re reading a book, your thoughts, it’s easy to get stuck in some rabbit hole. “Oh, the world is this way, I’ve figured it out” — and really, you haven’t figured out anything. I realized I needed to work with some kind of teacher. Again, I found some group, I saw a flier, I wrote down the phone number, and I called them. They said “well, we meet every Tuesday and Sunday, come on over”. And it took me like a year or more before I actually went. I’m not a group person. But it was very important, and for about four years I practiced very intensively with a teacher. And then I moved, I left Chicago and I moved out West again. I’m still in contact with my teacher, and she actually lives very close to where I live now. Now that my life is getting a little more settled where I am, I think I… (pause) I’m a bad Buddhist (laughs).

Mostly because I have a resistance to groups. I know. I’ve always been all alone — I mean, I have my good friends, really good friends, but probably all my good friends have a resistance to groups too. I don’t… (pause) A teacher is important, I think, because her mind is very good and…

Xavier Guilbert : Did she get to read King-Cat Comics ?

John Porcellino : Yeah, yeah.

Xavier Guilbert : What did she think about both the content and the process itself ?

John Porcellino : (a pause) I don’t know.

Xavier Guilbert : Because I get the impression there’s some sort of cathartic aspect to it — even if it’s very positive. Maybe not as much positive as the absence of negativity.

John Porcellino : Yes, yes. I was talking to one of the people in the [PFC] workshop about this last night. To me, I don’t want it to be something like hippy, like “oh, everything is great”. Because everything is not great. There is a lot of really bad stuff, and I’ve spent — I still wake up some days, and the first thing in my mind is “fuck it, today, this is it, I’m gonna blow my brains out”. But the positivity was an attempt to keep an equilibrium. Like : “okay, yeah, this is shit, but there’s also this other stuff”. Or even, “there’s a way of living with this shit… that is constructive or positive”. I mean, to me (and different people got different things) that was the great thing about punk : punk didn’t sugarcoat the world, it was : “this fucking sucks. Look at this stuff going on…” Even as negative as it could be, just the fact of addressing it and engaging with that world was positive. That’s how I look at King-Cat. It’s my way of engaging with that, no matter what it is. If it’s great, that’s one thing ; if it’s shitty, that’s another thing ; but I’m still going to try to get to the essence of it. Not shy away from it, either way. If things are happy, I’ll write about things being happy. If things are awful, I’ll write about that. And they are both equal, and I don’t want one to… consume the other one.

Xavier Guilbert : There’s a moment in Map of my Heart (in King-Cat #57) where you reveal that you got divorced. Which kind of echoes what you wrote earlier (in King-Cat #55) : “[…] many, many things have happened. Part of me wants to tell you all about it, but mostly I feel like I don’t know what to say. And when I feel like I do know what to say, I have a hard time expressing it. So it goes.” There’s this whole question about how to put things out, and when to put them out. When it finds its place on the page, in a way, it means that you’ve been able to deal with it.

John Porcellino : Yeah, I… Comics are the way that I process my experience. (a pause)

Xavier Guilbert : I’m asking that, because I’ve had a few exchanges along those lines during interviews with cartoonists. French author Ambre told about his pages being like “dead skin”, and Belgian creator Benoît Jacques telling about a book being “out”, and wishing to move far, far away from it. (John laughs) Is it the same for you ?

John Porcellino : (a long pause) I’d say… even when I’m not drawing, I’m doing King-Cat. That’s what’s in my head. My life is doing King-Cat. So if I’m doing the dishes, I’m doing King-Cat. If I’m walking around, if I’m sitting here with you, this is doing King-Cat too. Doing the comics, and printing them and sending them out, is also doing King-Cat, but is part of this larger thing. (a pause)

Xavier Guilbert : That makes me think of this Buddhist tale. The Emperor orders one of his servant to go and ask a famous artist to draw him a picture of a cat. So the servant goes to see the artist, gives him the money, and the artist draws a superb picture of a cat in just a few strokes. The servant, seeing this, protests at the amount of money the artist should be paid — after all, it was just a few strokes, right ? The artist nods, saying nothing, but motions the servant to follow him and leads him to another part of the house. And there, he opens a door, and there’s a room that’s filled with thousands and thousands of drawings of a cat. The conclusion of the story being that the effort is not just in the result, but lies somewhere else.

John Porcellino : That’s for sure. The process of me doing King-Cat is very much — maybe not me doing something over and over again. But thinking about it — a lot. Writing a lot, and then, cutting things out. Mostly what I do is cut things out. If I have a story that I want to do, I’ll do what I call a “memory page”, and I’ll just sit and kind of turn off my mind, but write out every little, tiny, no matter how insignificant detail on this page. I’ll sit and I’ll look at it and go : “okay, this, this and this.” It’s chopping these things out until what’s left is just the core of this experience. (pause)

The earlier question, I don’t know how to answer it. It’s — I mean, doing comics is therapy to me. Because it allows me to engage with these things in a constructive way. I think at that time, during my divorce and things… this is going to sound contradictory, but I felt : “I want to talk about this, I want to tell the story, but I don’t know where it begins and ends.” I just didn’t know how to approach it in a public sense. And also, I was ashamed — that my marriage failed. I felt like a failure, I was embarrassed. I kind of kept it hidden. Of course, my family knew, and my close friends, but even the people I worked with — not that I was that close to them, but I was… I just didn’t know what to say. It was a bad time, it took me a while to figure out how to talk about this.

And even then, in my comics, I was writing about it, but in a very oblique way. Maybe if you knew what was going on, you’d be able to see it : “okay, I think he’s talking about that here.” That’s part of the notes in the back of the book too. It gives you some kind of context. Because I do leave a lot out. Consciously, I’d leave it out. It helps.

Like I said, I realized it’s gratifying and strange to me that I have readers who are willing, who are interested. To me, the notes are… if I had an artist that I was very fascinated by, and I had been reading their work for a long time, that information would be interesting to me. It was hard to make that decision, because it sounds self-aggrandizing. Or like : “everybody should know all those little things about my life”. It was hard to — but I felt that if it was somebody else, I would like to read that. I’d be curious. Especially when the stories are about their life.

Xavier Guilbert : Do you still have this very personal connection with some of your readers ?

John Porcellino : Oh yeah. Yeah. I have readers who started reading King-Cat when they were 13 years old, and now they’ve got kids. (laugh) And I still hear from them. I send out the new King-Cat, and I get a letter back from them. I know about their lives to a certain degree. Going back to earlier, talking about art and stuff, that was why I… When I would make a painting and hang it out on a wall, and somebody would come in and look at it… actually, my whole thing with art was I wanted to communicate. In a two-way communication. I wanted to have some experience of life, share it with other people, and then hear back from them, and maybe go back-and-forth. I wanted there to be a personal connection. That’s what all my art has been about, it has been about connecting with people. It is a more personal… with some readers, at least. It doesn’t have to be that way all the time. But it’s important to me.

I realized this a couple of years ago. I was ill for about a decade. My health was very poor, it was hard to travel. At a certain point, I guess it was 2007 or so, my health was getting a little bit better, I started — I want to go out, go out on the road. And I’ve been going on the road ever since then. It’s slowing down now, but… once I went out and I would go to Baltimore or some of these cities and do a signing and talk to people. Talk about my comics, show my comics and talk, and people would come up to me and talk to me afterwards. I was like : “oh yeah, that’s why I do this.” Because when I was a kid, I wanted to express myself, I had this urge to share things but I was so shy and self-conscious, and through making ‘zines, through making my art, I found a way to share that with other people, and then get this thing back. And as soon as I went back on the road, it was good, because after all of those years of being sick and isolated — you lose track. I’m still doing this thing, but I don’t know why. Why am I even doing this anymore ? Then I went on the road and met the readers again, I was : “Oh yeah. I do this because I want a connection with people.” That sounds again kinda hippy, but it’s true. It’s nice to me that I have that relationship.

On the other hand, it’s hard sometimes to keep up with all the emails. (laughs)

Xavier Guilbert : That was also one of my questions — you have a blog since January 2010. Was that the inevitable progression of time and technology taking over ? Back around 2006, you mention something about the “dreaded Internet”. (John laughs) Also, considering that King-Cat has been your main channel of communicating with your readers, how do you see the blog ?

John Porcellino : Well, everything I’ve done on the Internet has been… grudgingly. Like : “Okay, well, I really need to do this.” I got on Facebook because — that’s how everybody communicates now. A lot of people don’t send emails, they just send you a message on Facebook. I think some people set up a King-Cat group on Facebook, and I would say — “tell them that the new issue is out” or something. At some point, I thought I should just be doing this myself.

The blog is nice, because… especially when I started, it was very exciting. Like you said, I’m down to getting one issue out a year or something, instead of every two weeks like in the early days. So it gives me the opportunity to put something out there very quickly. And keep that channel of communication open. Plus, I like to go on the road and take pictures and put them up there. It’s interesting, there’s this new issue that is coming out, there is some stuff that I wrote for the blog that is going to be in this issue. It makes sense. It would just have been in a notebook somewhere, and I would have put it in in the new issue. People wouldn’t have seen it. But now, it’s in a notebook and I put it on the blog, but it still needs to be in King-Cat. Not everything, but some things are… So now there’s some interplay between all that stuff.

Xavier Guilbert : Compared to your journal, you’ve been quite active on the blog.

John Porcellino : When I started out, I was : “I’ll do it twice a week !” It’s like King-Cat : the first couple of months, I got 40 blog posts.

Xavier Guilbert : There’s a lot of things there. There’s a long post about you moving from South Beloit…

John Porcellino : That article, or essay, or whatever it is, will be in King-Cat. That’s how the new King-Cat starts. Maybe a lot of my readers have already read it there, but it needs to be in King-Cat too. That’s the permanent place. That’s where it would have been, if I didn’t have the blog. That article would have started the new King-Cat.

Xavier Guilbert : Will it be handwritten, or typed ?

John Porcellino : I handwrote it. (pause) In some way, I don’t keep a journal, but I have stacks of notebooks. They are not like : “Dear Diary, I did this today…”, it’s lists of things and ideas, or phrases that somebody would say and I’d write it down because I like the way it sounds, or little sketches. They are more workbooks. When I did the Journal, I consciously told myself : this is not for the public. So I can be perfectly honest, I can say whatever I want to say, it doesn’t have to be beautiful or fine, or anything. But still, a lot of the Journal stuff ended up in King-Cat as well.

Xavier Guilbert : The Journal is regularly mentioned in the notes.

John Porcellino : And in Map of my Heart I included Journal entries. Because there was an honesty to them. Even though I did end up printing some of them, the intention was : nobody will see these, I’m doing this for myself. And I can be honest, I don’t have to hide anything. Because of that honesty, to me there was some powerful things there, that — eventually, I did think I can share this with people.

I don’t hate the Internet, but I’m very much old-fashioned. I draw on paper. This week, I’ve been looking at people who were so computer-literate : they’d do their drawings and they’d scan it and Photoshop and move all these things around — I don’t know. I’m kind of envious of that skill, and at the same time it’s… it’s hard enough just to do this.

I like the fact that the Internet has been able to connect me to people. I’ve always had readers in Europe, which was really exciting. But it has always been difficult. I mean, you’d send a letter, it’d take a week to get there, and then they would read it, then put it on their desk, and maybe a week later they would write a response and send it back to you, and this back-and-forth. Now you just email, and they answer two minutes later. That’s good, I like the communication of it, and I like the way it’s connected me. Especially with European readers. Like I said, I always had readers from over there, but it’s always difficult. Now, they send me email, they PayPal me the money, I put the thing in the mail the next day, it goes over there. It’s helped. Probably half my customers are from Europe. I like that, and I like being able, because I’m obsessive about things and history and information, I like to be able to type in something and — pof, everything you need to know is there. But that’s overwhelming too, I have to be careful. Otherwise, one thing leading to another, I’d be online all time learning about trivial things. (laughs)

Xavier Guilbert : I know exactly what you mean. So this next issue, #74, is nearly done ?

John Porcellino : Yeah, I tried to get it done for this festival [Autoptic] Sunday. I was staying up all night, and I realized — I wasn’t going to get it done, but I thought : if I come here, I can do the workshop during the day, and then at night I can go and work on the pages, clean them up, I found a printer here in Minneapolis so I could print it out. But I haven’t had a vacation — ever. I mean, we do a lot of work [at PFC], but it is fun. I just wanna go, be with these people and do these things, and not worry about that. Everything is done except the cover. It will probably out in a couple of — well, the printing process takes longer. Probably a month from now, hopefully. Knock on wood, it will be out.

And I’m working on a book for Drawn & Quarterly, that’s all new material. It’s three stories, and it’s about my health problems. Both the physical and the mental health.

Xavier Guilbert : Is it the first time you’re doing something that hasn’t been in King-Cat ?

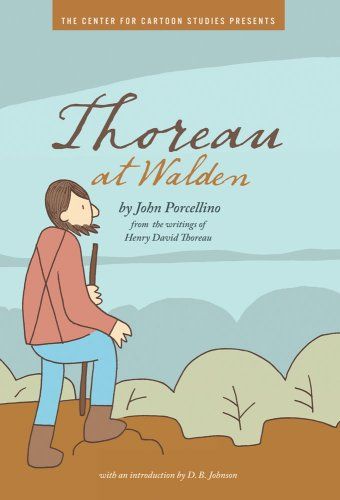

John Porcellino : Yeah, I mean, I did that book Thoreau at Walden. But not my personal comics.

Xavier Guilbert : One funny thing about Thoreau at Walden, speaking about the Internet, is that it isn’t even mentioned on your Wikipedia page. It’s not listed, as if, for some reason.

John Porcellino : The Wikipedia thing is, it’s Wikipedia.

Xavier Guilbert : What I mean, is that it’s only afterwards that I realized it wasn’t there.

John Porcellino : To me, the Thoreau book is just as deeply personal as any other thing.

Xavier Guilbert : Looking at the theme, it just makes sense. Like Zen Buddhism.

John Porcellino : There are three things that make me feel better when I’m really depressed : punk-rock, zen, and Thoreau. Those are my Big Three. When I’m feeling depressed or upset, I go to these places, and they remind me : “oh yeah, okay. Calm down.” Reminds me of who I am.

This book, the new book, is kind of an experiment. I have a number of longer stories — I have one that’s written, I just need to ink it, that I drew… seven years ago, I just never finished it. Never inked it. So the thought was to try and do collections of King-Cat — there’s another collection that could be ready to go any time. But if I have these longer stories, to try and do a Perfect Example length thing that would just appear in book form. We’ll see, this is the first one of those, and I’ll see how it goes.

It’s been interesting, because King-Cat is definitely — this is my focus. This is my ground that I come back to, that I want to always have. But the books are good too. And I love books as much as I love ‘zines. I appreciate having the books out there. They are a little bit different, but still part of the same thing. Like I said, we’ll see. When I started doing the books, it was an experiment. Perfect Example was just an experiment : let’s make this a book and see what happens.

Xavier Guilbert : Thinking about what we started with — saying that doing comics was okay as long as it was below the radar — looking at the King-Cat Classix book : it’s a big book with a dust jacket, it gives the whole thing gravitas, in a way. I suppose people discovered your work with that, right ?

John Porcellino : Oh, sure. And that was the whole thing with the books. When I say it was an experiment… I do the ‘zines, and they reach a certain number of people, but in some sense they are self-limiting. They are not going to reach everybody, necessarily. My interest with the books was finding other people who would be interested in my work, who, if they picked up a ‘zine, they wouldn’t — but if it’s in a book form… not tricking them, but that’s the form they need it to be in to be able to enter in. I felt a little bit funny about that book, because it’s an expensive book and it’s hard cover — but at the same time, I love books and I wanted it to be a nice book. I actually did the math : King-Cat is 32 pages, for $3, so roughly 10 cents a page. King-Cat Classix is 384 pages for $30, so it’s actually a better deal, than getting the ‘zine. So I was like — okay, that’s fine. (pause) It’s nice to have a book like that. (pause) I think having a book like that helped people, some people, maybe, think… “if there’s a book like this, maybe I should look at it and take it seriously or something.” I don’t know. I don’t know how that goes, but I think it was part of it. “Here is this book, it’s by Drawn & Quarterly, they publish good work, maybe this is good work too, I guess I should find out, we’ll see”. (laugh)

[Interview conducted on August 17, 2013 in Minneapolis, during PFC#4]

l’autre bande dessinée

l’autre bande dessinée