Igarashi Daisuke

With his fragile line, his magical stories and the nostalgia for a lost Japan, Igarashi Daisuke is one of the authors revealed by IKKI magazine, the experimentation laboratory of Japanese publisher Shôgakkan. Of course, defying all expectations, Igarashi Daisuke (a short but energetic and decided fellow) will answer in an incredibly fast flow of speech the questions of this bewildered interviewer. An encounter, in record time.

Xavier Guilbert : How long is your manga-ka carrier so far ?

Igarashi Daisuke : Something about ten years. Let’s see, since 1993 ? So yes, fifteen years.

XG : Was that something you ambitionned originally ?

ID : Yes. In fact, at the very beginning, I was very much attracted by drawing, and then … when I was drawing a scene that had touched me, with a single illustration, it was difficult for me to get accross a message. So very quickly, I felt the need to add other pictures — also, to represent changes, since when one uses his eyes, it is the changes that are important, little by little I grew closer to comic books.

XG : Nature seems to be a recurring as well as an important theme in your works. Where are you from originally ?

ID : I … in fact, I was born in Saitama, in the suburbs of Tôkyô.

XG : Then where does this interest for nature that pervades your books, as opposed to urban life, comes from ? ?

ID : In the city I grew up, there was an old temple. And in this temple there was a little grove with trees that were many hundred year old, and every day I used to spend some time over there, playing. And — how can I say ? When I was playing every day among those trees, I was struck by their beauty, and I wanted and tried to see if I could express some of this beauty on paper. This is how I got started.

XG : You made your debut with Hanashippanashi, which is a collection of short stories, but later on you moved on to longer narratives. Does that correspond to a growing self-confidence ?

ID : At the beginning, I … in fact, when I started doing comics, I wondered what style I wanted to use, what themes I could best express. That’s how I turned to the short story structure for Hanashippanashi. I did that for two years, and then I realized there were some things I could not tell in this way. This is why I decided to turn to longer narratives, to try and find new things in me, and see if I could express them. And this is what led me to do longer stories.

XG : Reading Hanashippanashi, your vision of childhood reminded me a lot of GoGo Monster by Matsumoto Taiyô. And of course, your interest for nature also brings to mind the works of Miyazaki Hayao. Were you influenced by those two artists ?

ID : Regarding Miyazaki Hayao, of course, it’s … I’ve been watching his movies since I was a kid, I think he influenced me, without a doubt. When it comes to Matsumoto Taiyô, in fact — until recently, I hadn’t read anything from him, so I don’t think he was an influence in any way. Yet, I knew of his art, and that was a style that I really liked, but I hadn’t read anything from him. So no, no influence there. But Matsumoto Taiyô’s art is not only very stylish, but moreover his stories are compelling. And I think that’s rather rare in Japan, and I have a lot of respect for him.

XG : In Hanashippanashi, there is also a lot of fondness for the shita-machi,[1] is that something you feel some nostalgia for ?

ID : The atmostphere present in Hanashippanashi is based on the places I love. And in particular the city where I grew up, the city where my parents used to live, places I visited and that I liked, I put all of this in Hanashippanashi. So … that being said, as time passed the city I was born has changed, and the places that I liked have disappeared, little by little. And I tried and kept their memory alive in my books.

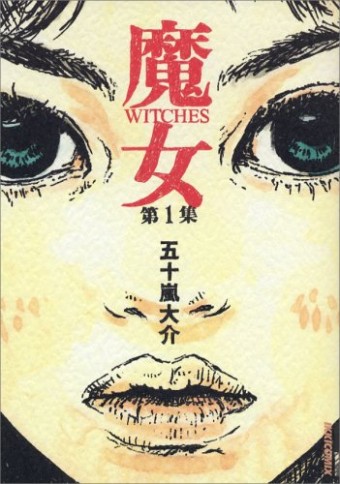

XG : In Majo, the story is set in a country that, even if there are some common points with ancient Japan, is still very different. Why this change ?

ID : Indeed, I like ancient Japan a lot, like for instance the Matsuri[2] and I went all across the country to see different ones. And even if the climat changes a lot, from Okinawa where it’s very hot, to Tôhoku where it’s very cold, I noticed that all those matsuri refer to a common core, similar things. And I started to wonder why, and while searching and comparing with celebrations from other parts of the world, that a lot of them shared the same essence. And — how can I say ? Maybe that, a long time ago, there was a sort of community that used to share a similar way of thinking, across the world. And that’s what I tried to express, by talking about another country than Japan.

XG : In Majo still, the main characters are women, and bearers of magic. To the contrary, the male characteres are destructive and followers of science. Was that a conscious opposition on your part ?

ID : Indeed, I do have the impression that women are closer to the things of nature. Of course, there is the fact that they bear children, but from a tradition standpoint, women have always been seen as closer. And that’s why I chose male characters to represent their less positive counterparts.

XG : Were you also making references to traditional Japanese legends, with for instance foxes turning into humans, most of the time into women ?

ID : Exactly. In ancient Japan — but that might also be the case elsewhere — shamans used to be women. And I think that for me, that was a very strong image.

XG : Two years ago, you participated in the collective Japan, for which you produced a story talking about traditional Japan. Was that part of the brief ? How was the experience ?

ID : Well, as the brief was to do something about your own region, and as I was then living in the Iwate-ken,[3] they asked me to do a story about Iwate. I started to think about what I could tell about Iwate-ken, and of course I considered doing something contemporary. But then I learned that for that collective Japon, a certain number of French authors had come to Japan and had to write about their experience there. And most likely, talk about contemporary Japan. So that’s why I then decided to turn towards something more ancient, that a visitor today could not get to see.

XG : That’s the kind of angle that almost all Japanese authors of the book have chosen, and it nearly gives an impression of nostalgia.

ID : They must have come to the same conclusion as I. That as the French authors were going to talk about today’s Japan, might as well do something different.

XG : With Little Forest, you propose a sort of “guide for the countryside life”. Is it based on personal experience ?

ID : Yes, I went to live for three years in the deep countryside, in a small town of the Iwate-ken. And there, I had to manage and work in the fields and the rice paddies. And that’s an experience I really enjoyed, and I wanted to share it.

XG : And you didn’t encounter any problem presenting that project to your publisher ?

ID : In fact, for Little Forest, it’s when I told them that I was going to move to that kind of area that my publisher proposed that I do a comic on the subject.

XG : On that subject, you currently publish in IKKI magazine, which is a very peculiar space in the Japanese publishing landscape. Does it give you a lot of freedom ?

ID : Definitely. I can say that they let me do almost anything I want.

XG : Your most recent work is Kaijû no Kodomo, is it dealing again with the same nature-related themes ?

ID : Kaijû no Kodomo is a story around the theme of the sea. It’s the story of a young, modern-day Japan girl, who is going to meet two young boys who have been raised by dugongs. And meeting those two kids, she will end up uncovering the mysteries of the sea.

XG : So this is another story about the discovery of nature ?

ID : Yes, I wanted to show the beauty, the greatness and the depth of the sea.

XG : Again, is that something that corresponds to an aspiration of yours ? You are not exactly an edokko,[4] but close …

ID : True, there is no sea in Saitama, but I’ve always been attracted to the sea.

XG : How many volumes have you done ?

ID : So far, two.

XG : How many do you foresee, in total ?

ID : As I see it today, there should be five volumes in total. But as I — how can I say ? I don’t follow a set plan, I build the story as I go by, and if there are other images that come to me, maybe it might end up a little longer. All is not decided yet.

XG : Which would make it your longer story by far.

ID : Right.

XG : And obviously, you seem to feel more confident about that.

ID : To be honest, I don’t know yet how this story will turn out. But I like the idea of a challenge, and I’m doing my best.

XG : In Hanashippanashi or Little Forest, you used to deal with the small things of everyday life. That aspect was also present, although less prominently, in Majo. How do you manage to include those preoccupations in a longer narrative ?

ID : When I work on a short story, I start of with the idea I have in mind, and I try and keep only what is absolutely necessary by removing progressively the rest. This time, with Kaijû no Kodomo, I don’t edit anything, and I try to draw as much as possible what I have in mind.

XG : For Little Forest, you went to live in the countryside. This time, do you intend to move and live by the sea ?

ID : I’ve been attracted to the sea for a long time, and I’ve been on vacation in Okinawa on many occasions, and those stays have been a source of inspiration for me. But this time, very soon — next month… I think, I’m indeed going to move and live on the seaside.

XG : Again, in the idea of sharing your own experience ?

ID : Yes, that’s what I would like to do.

[Interview conducted in Angoulême, on January 26, 2008.]

Notes

- Litterally “the lower city”. Historically, this term was used to describe the districts where artisans and merchants used to live in Tôkyô, as opposed to the aristocratic yamanote (“towards the mountain”). Today, this expression is used to describe small town life, lively and full of human warmth.

- Traditional Japanese festivals.

- One of the 47 prefectures of Japan, located in the Tôhok area, in the northern part of Honshû, the main island of the Japanese archipel.

- Litterally, «kid from Edo». Usually describes a streetwise kid from the city.

l’autre bande dessinée

l’autre bande dessinée