Numerology, 2006 Edition

As the last sprint to Angouleme draws near, and after Gilles Ratier’s report that heralded the “maturation” of the comic book market, here comes the press announcement of study institute GfK, coming with a title of dubious taste : “between sushi and mussels and fries” — a more or less witty way to confirm what has now been widely accepted, to wit the (harmonious ?) cohabitation of manga and ye good ole franco-belgian bande dessinée.

Here at du9, we were aiming at bringing something to the table with some new figures, to follow-up on last year’s article on the same subject. Unfortunately, our various attempts at getting our hands on sales data have been unsuccessful, as this is a sensitive domain, and unless you’re ready provide some hard cash in exchange for the hard facts, you won’t learn much.[1] Never to be taken down by such a trifling detail, we intend to make up this lack of new figures with a new approach — starting with what can be deduced from the few information provided by GfK.

A little cuisine, to get some figures

Coming with the press announcement mentioned above, GfK also provides two charts with the best-selling titles and series for 2006. Of course, instead of sales figures, you’ll find “indices”, a clever way to provide information without actually revealing it. Still … still, the announcement mentions the sales of the top two titles (Titeuf volume 11 with 646,000 copies, and the second volume of the revived Lucky Luke with 268,000 copies). Let’s check : it works, number two is indeed selling 41 % of number one — so now we can estimate (approximately though, but within a realistic range) this top 20 chart.

As for the series, things get a little more complicated, but a little trick allows to get by. Looking closely at the title chart, you can notice that the six most recent volumes of Naruto are listed, alongside the first two volumes of the series, with sales indices around 13-15 %. Taking into account a slight erosion among the volumes 3 to 20, we can suppose that each one of this volumes will reach sales indices around 8-9 % — or a total indice around 260-278 % for the series overall, or sales around 1,7-1,8 million copies. We’re done.

Let’s throw in the average retail prices in the two charts, for good measure, so that we can also study what happens when looking at value. It’s ready.

A dash of analysis, to sort out the best-sellers

Manga are here, without a doubt — up to 36.3 % of the total volume sales, according to GfK. But both in the title chart and in the series chart, it is clear that there is Naruto, and there is the rest of the pack. In fact, a quick estimate shows that Naruto alone represents about 10 % of the manga market in France. Worse — the five top-selling manga series[2] control a third of the total manga sales — equally distributed among Kana/Dargaud (15 %) and Glénat (15 %), Kurokawa getting the scraps (3 %). Definitely a stronger concentration than on the two other segments tracked by GfK (youth comic books, and adult comic books), where the five top-selling series represent a more reasonable 20 % of total sales.

In fact, the “domination” of those manga series is based on the consitution of the cative and loyal audience, thanks tho a regular publication schedule.[3] Thus, the top 20 titles chart includes the six most recent volumes of Naruto, nearly in their order of publication, which suggests a population of 110,000 fans — or an audience similar to that of series like Les Profs or Trolls de Troy, far behind the last Titeuf book with 626,000 copies sold.

This dynamic is also present, with a greater amplitude, among franco-belgian comic books as, in an interesting coincidence, the top sales for 2004 were … the tenth volume of Titeuf with 835,200 copies and the first volume of the new adventures of Lucky Luke with 414,400 copies.[4] Things are very similar in the lower part of the chat, with Les Profs volume 9 (around 100,000 copies) enjoying a performance very similar to that of the volume 8 last year (around 95,000 copies).

Actually, “serial successes” dominate the top 20 title chart, as it includes only two non-sequel titles that we will qualify as “marketing books” for lack of originality : La Face Karchée de Sarkozy which benefits from its political content in line with the coming elections, and the first tome of the TV-show adaptation Kaamelott by Casterman — no more hiding behind its Jungle imprint for licensed products.

Considering value sales with such a limited top does not bring much, except it logically diminishes the share of manga, which retail for a much lower average price compared to the other segments of the market (very simply put, manga titles retail for around 6€ / youth comic books around 8.75€ / adult comic books around 10.50€). Thus, despite the different volume sales, the two market-drivers Naruto and Titeuf end up neck-to-neck with revenues estimated around 10.5 million euros each.

This also raises the question of the few comic-related magazines that remain on the market. Indeed, the press has covered the problems of L’Echo des Savanes awaiting a potential takeover. But even considering failing sales reaching only 65 % of its estimated print run of 55,000 copies, this still represents a yearly revenue of 1.7 million euros — comparable to what Détective Conan (aka Case Closed, the series ranked #20 in the top 20 chart) generates.

From the publisher’s point of view, it is clear that a magazine implies different structures as well as different business models. But that does not change the fact that both magazines and comic books are purchased by the same readers, with a limited budget. The former spearheads of publishers, margazines are now seen as competing with comic book album sales, to the point that some ambitious attempts are seriously hindered by the will to promote, again and again, the album format. To wit the lack of clarity around Shogun Mag and its serialized stories that will be collected, without knowing precisely if the serialization will carry on afterwards, or if the magazine will end up being simply a window into the publisher’s catalog.[5] Not an ideal situation to ensure the readers’ fidelity…

A pinch of estimate, to gauge the publishers’ weight

Contraty to what we had done last year, it is difficult this year to statuate on the respective position of the major publishers. The study of the series chart only allows to make out some general trends, with the Média Participations and (Dupuis/Dargaud/Le Lombard/Kana) Glénat groups (Glénat/Vents d’Ouest) getting the lion’s share with about a third of the sales each. Behind them, the Hachette group with about 10 % of the sales, and finally a rough tie between MC Productions (aka Soleil and its satellites), Delcourt and Flammarion (with Casterman).

In order to refine a little this outlook on the market, we will have to resort to using the print runs mentioned in Gilles Ratier’s report — but keeping in mind the limits of this approach. First, those print runs are to be handled with care, considering that 1. they are declarative and therefore depend on the honesty of the publishers who communicate around them, and 2. the list is not exhaustive and is based on its author’s connections. Second, those print runs are not directly representative of the actual sales, but rather of the publishers’ ambitions regarding the corresponding titles. This said, they can give a rough idea of the market structure, as we hope to show.

We will not that 195 books benefit from an important push — with initial runs over 30,000 copies. But it becomes quickly obvious that the Média Participations group represents 40 % of those books, rising even to 50 % when limiting this analysis to initial runs over 60,000 copies — a share unchanged against 2005.[6]

In average (and on the basis of initial runs superior to 30,000 copies), the print runs of non-Asian comic books are around 100,000 for the five biggest groups if we exclude the Titeuf “monster” which represents alone nearly 50 % of the cumulated volume of the largest print runs of the Glénat stable (including 34 titles). Manga initial print runs are more modest, averaging between 50,000 and 60,000 copies.

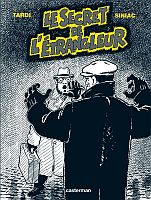

Taking away the manga titles, 2006 has been a “rich” year for original creations, with 11 large initial print runs (over 30,000 copies) versus 6 in 2005. But original creations do not mean new talents : indeed, the largest print run for a “creation” goes to Tardi and his Secret de l’Etrangleur, followed by Magasin Général by Loisel and Tripp, who are not exactly beginners. La Face Karchée de Sarkozy (a risk-free title in the current political context) and Shirley et Dino (by Margerin, another old timer) complete the top four “creations” with initial runs over 100,000 copies.

There is no doubt here that the keyword is security.

For the rest of the pack, it’s the same structure all over again, or close : slightly less long-running series with more than 10 volumes (25 versus 35) compensated by more series aiming for longevity (46 versus 34), with a stable total (71 for 69) ; on other fronts, as many licenced products (9 versus 8) like Zidane or SAS, and as many … erm, “marketing” products (10 versus 9) like the unforgettable joke collections on blondes / firemen / teachers / rugbymen.

By extrapolating print runs to calculate theoretical market shares, we find confirmed the hierarchy outlined in the series chart : Média Participations the unchallenged leader (41 %), far ahead of Glénat (23 %), Flammarion (8 %), MC Productions (7 %) and Delcourt (6 %).

The share of manga in the cumulated total of the largest print runs (30 %) is slightly lower than the sales figures given by GfK — a slight offset that can be explained by the long-term sale of long-running series, such as for Dragon Ball, still the #2 series in top.[7]

A sprinkle of perspective, to flesh out some major trends

With the growing number of new titles being released on the market each year, there have been frequent mentions of surproduction, a probable sign of imminent crisis. And industry actors worry about the high rotation of books, explaining how today, an album has about a week to realize its turnover, before being returned to the publisher. Let things be clear : the inflation in production is not a monopoly of the comic book industry, but touches the entire cultural sphere. From the available TV channels to the movies being released in theaters, from music CDs to the literary ouput, it has never been produced as much culture as during the recent years.

The number of new releases per year prove this : even if manga titles have shown a strong increase (new releases seeing a sixfold increase between 2000 and 2006), all other segment have seen a doubling of their production over the same period — be it US comics, major publishers or small press publishers.

We touch here “the long tail effect”.

Supported by the global accessibility allowed by the Internet, this effect also corresponds to a paradigm shift in social dynamics : in the past, a little group of “trend-setters” used to decide what what “in” or “out”, while now it is the mass that elects its favorites. The result is this “long tail” behind the vertiginous peak of the popular successes, with a scattering towards “niche” products allowing the development of a true diversity and a real cultural richness.

On the economical level, consequences are clear : if you want to benefit from the “long tail”, apart from the blockbusters, you have to be prepared to sell less books, but on more references. Which does not equal economical unsuccess — this is one of the most surprising aspect of this phenomenon : cumulated sales of the “niche” products are actually more important the sales of the blockbusters.

Considering initial print runs, the “long tail effect” is clearly obvious — as is shown on the graph on the right, covering the 2006 releases. This trend is confirmed by the high market concentrations on the best-selling series observed above.

Faced with this market mutation (which, again, concerns the whole cultural sphere), two different approaches are possible : reduce the number of references to focus only on the best-sellers ; or increase the number of references to satisfy all readers. In this latter approach lie the reasons behind the success of the cultural megastores, offline (the Fnac retail network, the huge Furet du Nord bookstore) as well as online (Amazon or iTunes and their catalogs proposing millions of titles). This has also been the case on the publisher side, with on one hand the constitution of strong publishing groups trying to position best-sellers on each and every identified segments, and on the other hand small structures with a specific and often confidential production, but which could, in the long run, benefit from the possibilities opened by online stores.

For the comic book specialist stores, the problem is more complicated. Sticking to the best-sellers is playing it safe, but also means becoming exposed (through a lack of diversity/specificity of the offer) to the growing competition of supermarkets. Yet, increasing the number of references is not always possible, due to limitations of available space or an inadequate stocking system.[8] Remains the solution of earning the fidelity of your customers through personalized advices or specialization, placing a bet on the quality of a selection. But of course, that requires another set of talents than simple inventory skills.

A zest of criticism, to conclude and question

Considering the limited data we have at our disposal, we will not dare taking sides in the debate surrounding the crisis of the comic book industry — as we have seen previously, we need to reframe it in the context of a profound evolution of the consumption habits. The surrounding anxiety has a real basis, but should deal more with the durability of the existing editorial structures, rather than worry about the survival of the industry as a whole.

Indeed, the scattering of the sales across a large number of titles goes against an economy so far based on best-sellers and series dynamics. The question is to know whether the major groups will be able to adapt and innovate — a real challenge when managers as well as editors usually come from the industry itself, something that is often cited as a guarantee for quality. And changing long-established habits then becomes all the more difficult.

Furthermore, the arrival of manga has without a doubt strongly modified the European editorial landscape, while supporting and participating in the strong growth of the recent years. Better — manga have brought back to comics a young and/or feminine population which had so far no interest in them (feeling that the general franco-belgian production in its great majority was more than happy to return).

A quick roundup of Internet traffic on comic book-related websites is confounding : if we are to believe the rankings provided by Alexa,[9] three manga-dedicated websites (Manga-sanctuary, Manga-news and WebOtaku) are present in the top five and by far, a clear sign of a strong reader implication. (cf. the attached file, based on a fastidious information gathering on January 20, 2007, with no guarantee of exhaustivity)

Let’s go even further : where the Titeuf fan will only spend around 10€ every other year to purchase the latest album, the Naruto fan spends close to 36€ every year.

Among the reasons behind the manga appeal, we can mention a kind of teenage quest for identity, a quest that finds its resolution both within the thematics,[10] but also in the opposition to the parents’ values, in search for an “elsewhere” (crystallized in a certain vision of Japan) and a “difference” (of format, reading direction, etc.). And of course, it is a small victory when adults have to confess their confusion, not knowing how to read or consider this object.

The industry has been quick to understand that this specificity is a key motivator for the teenage reader, and even quicker to jumb on the bandwagon[11] toward the manga marketing El Dorado — choosing the easy way by playing out this aspiration for difference : dedicated imprints with Japanese-sounding names, distinct communication (different websites for some publishers), magazines and specialised stores … the main idea being to preserve and foster the existence of a “manga-fan” community, in the hope of keeping the Golden Goose alive.

Moreover, broadening the manga readership will become a crucial challenge, as the release schedule of best-sellers such as Naruto will go down after catching up with the Japanese publication. From six volumes a year, it will go down to three or four, and profitability will decrease accordingly. And not much hope to come from new Asian revenue-makers — very few major series remained unsigned today.

Then, instead of waving the specter of the Yellow Peril and requiring a cultural exception, we should see there an opportunity and study the true reasons (beyond the teenage crisis) of this success. And, from there, build on establishing real connections and encourage this new, implicated and enthusiastic readership to try on the remainder of the production, Asian as well as non-Asian. Even if the market is stabilizing this year,[12] it is clear that comic book reading has reached a high over the recent years. It should be a reason to rejoice, not to worry.

To conclude, it could seem strange that, on a website dedicated to “the other bande dessinée”, this analysis do not spend more time on the case of the “other publishers”. The reason is simple : market analysis deals with global masses, and thinks in terms of revenue and marketing, shareholders’ satisfaction and profitability rates ; the “other publishers” often limit their ambition to releasing good books.

Thus, in his report, Gilles Ratier suggests that sales around 7,000 copies would be a strict minimum, indicating that “this remains profitable for a few publishers, but not as much for the author.” In his recent book Un objet culturel non identifié, Thierry Groensteen quotes Etienne Robial, then owner of Futuropolis : “I publish some books with runs of 500 copies, and they are profitable. The mainstream public never sees those books, does not even know they exist, but they are sold out within eight days ! When I’m finished paying the authors, I still have money left.”

Two different visions that correspond to two different worlds existing side by side, the economic reality and challenges of the first without much relation with those of the other.

Notes

- And although du9 is ripe with faith and enthusiasm, there are limits to our funding in our Quest for Truth. But if a good Samaritan were to have access to this data, and was willing to share in order to support us in this direction, do not hesitate to contact this article’s author. Discretion guaranteed.

- Naruto, Dragon Ball, One Piece, FullMetal Alchemist and Samurai Deeper Kyo. Note that FullMetal Alchemist is the only series counting less than 25 volumes.

- This is obvious when looking at the publication schedule across the year. The manga segment remains very stable, with an average of 90 new titles per month, from a minimum in July (81 titles) to a maximum in November (110 titles) or June (112 titles).

For reference, major publishers and small press publishers alike know more important fluctuations, with a ratio as high as 8 :1. For instance, major publishers cumulate an average of 75 new titles per month, with a minimum in July (14) and December (16), and a maximum in September (111) ; and for small press publishers, an average of 40 new titles per month, with a minimum in August (8) and a maximum in November (68). - Note that the 2006 volumes of those two titles were released later (October 2006), hence the lower sales figures. For reference, Titeuf volume 10 was released in August 2004, and Lucky Luke volume 1 in September 2004.

- To be completely precise on the subject, things are even hazier. On one hand, the TPBs should include bonuses and previously unpublished pages, but depending on the titles, the number of missing pages vary between 24 and 72. It seems a lot for bonuses, so we will have to wait until the books are published to know exactly where to stand.

On the other hand, only four months after the launch of the magazine, the publisher evokes the possibility of turning it into two different periodicals more precisely targeted, with a “shônen” and a “seinen” edition. Again, nothing confirmed here, but the whole thing is far from being a carefully planned project. - It is also interesting to note that, among the largest initial runs of the Média Participations group, two books out of five are due to its “manga” label Kana — a proportion in perfect adequation with the market structure, or how to adapt the offer to the demand.

- For reference, the Dragon Ball series published by Glénat regroups no less than 81 volumes across three different editions (normal, deluxe and complete).

- The stores where I regularly “roam” remain attached to bins for albums, certainly a comfortable continuity for the regular customers, but limits the number of books that could be proposed in shelves. Indeed, shelves are sometimes present, but instead of holding books, they are dedicated to “para-comics” paraphernalia of sometimes dubious taste, but always far more profitable.

- An Amazon subsidiary, creator of a toolbar that doubles as an Internet traffic tracker. Even if the toolbar is so far only available in English, Alexa considers it tracks over 10 million websurfers around the globe.

- Shônen titles, for instance, often follow an initiatic journey, and address a large palette of subjects, including the discovery of sexuality. A sexuality that is practically absent from the great classics of the franco-belgian production, (Tintin, Astérix, Lucky Luke, Spirou, etc.), but which is without a doubt a key factor behind the success of series such as Lanfeust de Troy.

- Cf. De Bonnes Guerres.

- And this, in the absence of a “monster” such as the latest Astérix, which represented alone 3 % of the total sales of the market in 2005.

l’autre bande dessinée

l’autre bande dessinée